Sexual misconduct allegations against California doctors rise sharply since #MeToo era began

The Berkeley pediatrician was treating a teenager for anxiety and panic attacks. A few months into his therapy appointments, he began showing the boy pictures of men masturbating as well as other pornographic images, according to state documents.

During several appointments, the doctor instructed the boy to masturbate and watched as he did so. He later had the boy perform oral sex on him.

Late last year, the Medical Board of California stripped the doctor, Bayard Allmond, 84, of his license to practice.

Allmond is part of a growing wave of California doctors who have faced sexual misconduct allegations in the last two years.

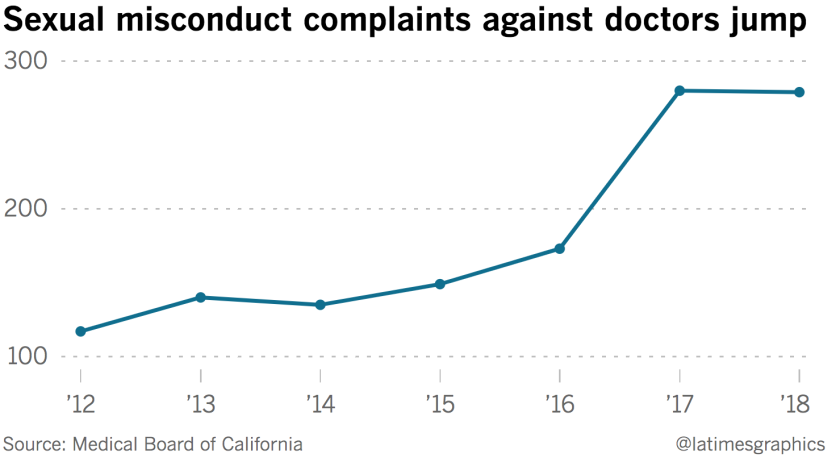

Since fall of 2017, the number of complaints against physicians for sexual misconduct has risen 62%, a jump that coincides with the beginning of the #MeToo movement, according to a Times analysis of California medical board data.

During that same time, medical boards across the country also noticed a surge in sexual misconduct complaints, according to Joe Knickrehm, spokesman for the nonprofit Federation of State Medical Boards, though figures were not available.

Many experts link the increase to societal shifts spurred by the #MeToo movement, which encouraged victims to speak out, as well as noteworthy abuse cases involving medical professionals.

In 2018, Larry Nassar, a former USA Gymnastics doctor, was sentenced to 40 to 175 years in prison for molesting young athletes. The same year, hundreds of women came forward to accuse former longtime USC gynecologist George Tyndall of inappropriate behavior. In June, former UCLA gynecologist James Heaps was charged with sexual battery and exploitation during his treatment of two patients at a university facility.

As these stories permeate, patients have become more vocal in the doctor’s office, seeking to know what physicians are doing each step of an exam, doctors say. They are also more willing to speak up if something bothers them, empowered by these recent revelations, said Dr. Sheryl Ross, an OB-GYN in Santa Monica.

“It’s a look, it’s a touch, it’s having a man rub up against you with an erection — it’s subtle things that I think women didn’t always have an understanding that this is inappropriate,” Ross said. “The days of just sitting back and having the doctor tell you what to do are gone.”

The California medical board, which licenses more than 140,000 physicians, has the power to take away a doctor’s license if it decides that person has acted inappropriately and violated the terms of their license. Anyone can file a misconduct complaint with the board, which will then be investigated by staff.

During the fiscal year that ended in June, the California medical board received 11,406 complaints against physicians and surgeons, the most it has ever received. Complaints of sexual misconduct, though small in number, are among the fastest growing type of allegation.

In fiscal year 2017-18, 280 complaints were filed against physicians for sexual misconduct, compared with 173 the previous year. In the 2018-19 fiscal year, there were 279.

The Times obtained data on sexual misconduct through public records requests to the medical board, which does not typically publicize sexual misconduct complaint numbers and has not yet published any data from the 2018-19 fiscal year.

The misconduct by Allmond, the Berkeley physician, occurred in 2016, but it appears the patient did not report it to police or the medical board until late 2017. Last year, Allmond pleaded no contest to a felony count of sending harmful matter to a minor with sexual intent.

Neither Allmond nor his lawyer could be reached for comment.

Medical board spokesman Carlos Villatoro said the board hasn’t changed policies or tried to round up more complaints against physicians, for sexual misconduct or anything else. However, the board “takes allegations of sexual misconduct very seriously,” he said in an email.

Since mid-2017, 23 physicians in California have lost their medical licenses because of sexual misconduct.

Often, those cases result from an ongoing criminal case against a doctor.

In June, the medical board revoked the license of Lake County nephrologist Moutaz Almawaldi after he was convicted of sexual battery. Earlier this year, the board stripped San Francisco psychiatrist Billy Lockhart of his license after he was convicted of possessing child pornography and sentenced to prison.

But such cases are likely not driving the increase in complaints to the medical board, experts say. Instead, it’s probably patients reporting the kind of misconduct they may have overlooked otherwise.

A patient confronted with inappropriate behavior that is perhaps subtle, or could be interpreted in different ways, may be emboldened by a culture that is increasingly saying these things are not OK, said Dr. James Marroquin, a bioethicist in University of Texas at Austin’s Dell Medical School.

“Where in the past she just kind of blew it off, if you have more publicity about the stories from Harvey Weinstein and others ... it might tip women to respond in a different way,” Marroquin said.

Marian Hollingsworth, a frequent critic of the board, agreed that Californians in particular may have recently learned about the medical board’s role in sanctioning doctors from following the cases against Tyndall and Heaps.

Yet Hollingsworth worries the increased complaints will not bring more actions against physicians. Just 4% of complaints turn into action against physicians, a figure that has dropped in recent years.

“The disciplines haven’t been proportional to the number of complaints,” Hollingsworth said.

Indeed, in both the 2016-17 and 2017-18 fiscal years, 21 doctors were disciplined for sexual misconduct. The figure dropped to 13 in the most recent fiscal year, according to medical board data.

A doctor whose license is revoked can apply for a new license in three years. Still, some physicians feel the board has overstepped.

The medical board revoked the license of Dr. Muhannad Hafi, who practiced in Santa Clara County, in December 2018 after two female patients accused him of sexual misconduct.

Hafi, however, maintains his innocence.

A criminal case involving the first patient, who accused him of touching her breasts and sticking an ungloved finger in her mouth, went to trial and Hafi was acquitted by a jury. Police did not file charges based on the second patient’s allegations that the doctor pressed his erect penis against her body.

In December, Hafi sued the medical board in San Francisco County Superior Court, arguing that taking away his license is “manifestly unjust and not supported by the weight of the evidence.” In June, a judge determined that the board had acted correctly and that the revocation will stand. Neither Hafi nor his attorney could be reached for comment.

Representatives from medical boards nationwide said in their annual survey last year that sexual harassment violations were among the most important topics to them, said Knickrehm, spokesman for the Federation of State Medical Boards.

In response, the agency launched a working group on sexual boundary violations last year. The group is studying state medical board policies and trends related to sexual misconduct by physicians and plans to share new recommendations in 2020, he said.

Richard Carpiano, a medical sociologist at UC Riverside, said that it’s vital the medical profession address its public reputation in the wake of these misconduct cases. Faith between the patient and the physician is uniquely important for the field, he said.

“For the medical profession, the trust between a patient and a doctor is the foundation,” he said.